(aka: 🤔 How does a bacterium manage to still be in your bloodstream right when a tick shows up to feed?)

Ticks are here for the blood party — they show up, suck blood, and leave.

If ticks are the bus, then Ehrlichia is the passenger in your bloodstream who’s standing at the curb with their suitcase, staring at the road like:

“C’mon… where’s my ride? I need to catch the next tick.” 😭🚌🧳

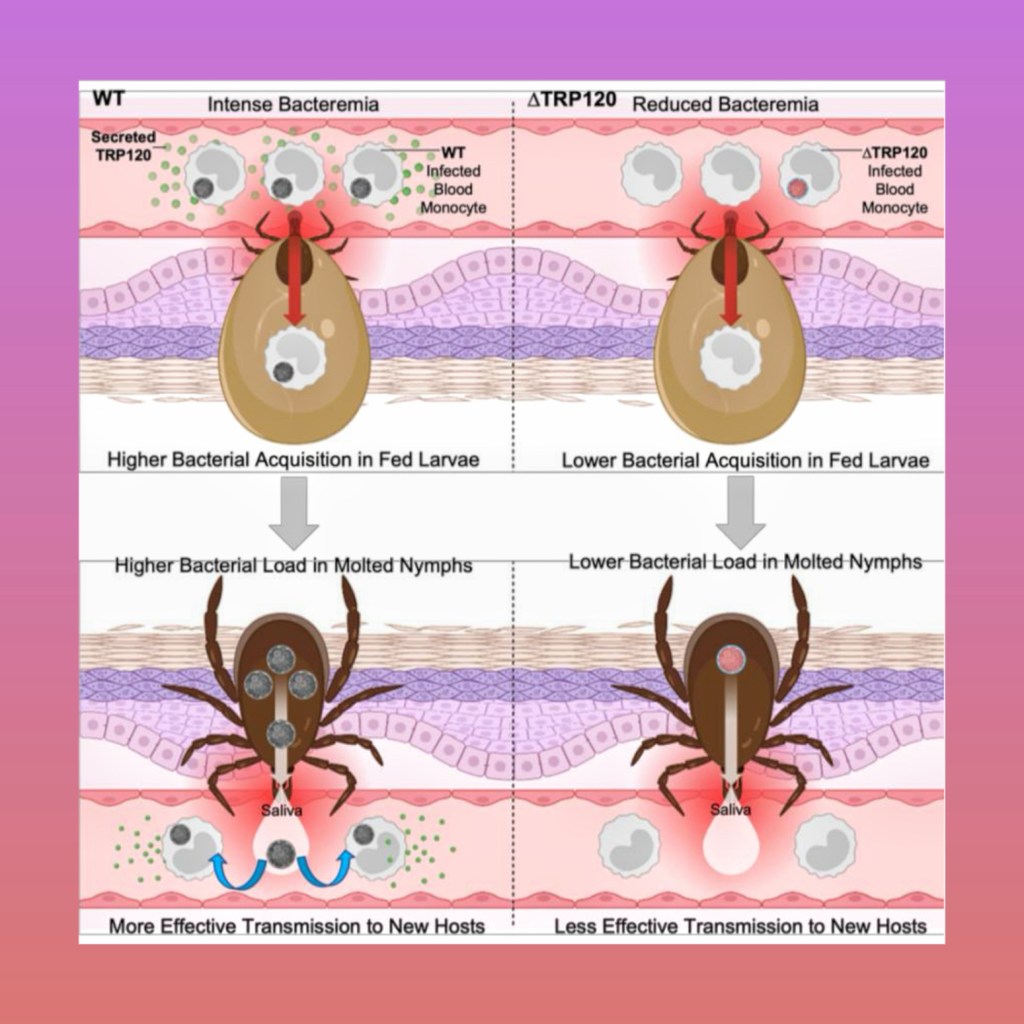

They’re not trying to “win” in your liver or spleen (even though… they definitely do a lot 😭) — their real goal is to stay circulating in the blood, because that’s the only place they can get picked up and hop into the next host.

And in my paper, I found one single bacterial protein that basically decides whether that blood-ride plan works.

Meet TRP120 — the bacterial “influencer” / “relationship manipulator” / “logistics manager” that helps Ehrlichia stay in the bloodstream long enough for ticks to pick it up.

🦠 First, what is Ehrlichia?

Ehrlichia is a tick-borne bacteria that lives inside immune cells (especially monocytes / macrophages), and it can cause a serious illness called human ehrlichiosis.

It has a very specific lifestyle: it infects mammals, infects ticks, and keeps bouncing back and forth between the two to survive.

So the bacteria has a problem to solve:

“How do I stay in the blood 🩸 long enough to get picked up by a tick?”

That’s where TRP120 comes in.

🧪 What we did (the “one protein difference” experiment)

We compared:

• WT (wild type) bacteria = normal, has TRP120

• ΔTRP120 mutant = missing TRP120

Then we tested them from mammalian cell cultures to tick cells, in vivo infection in mice, and ultimately tick feeding. 👀

🔥 The plot twist: TRP120 is NOT required for disease… it’s required for being in the blood

Here’s the most dramatic part:

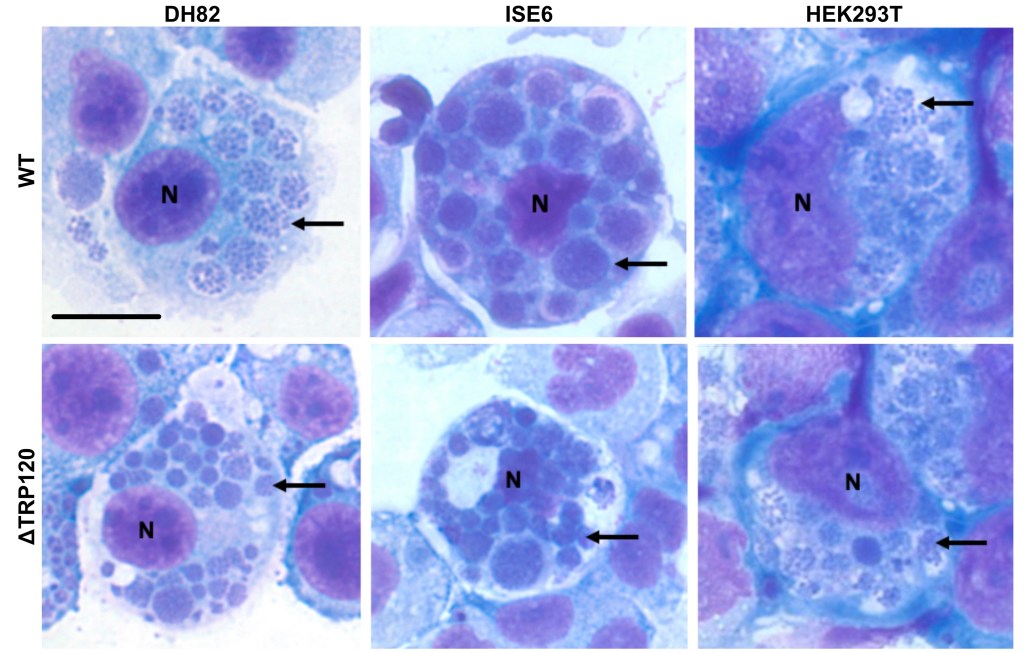

🧫 In cell cultures:

Both WT and ΔTRP120 grew just fine. No big difference.

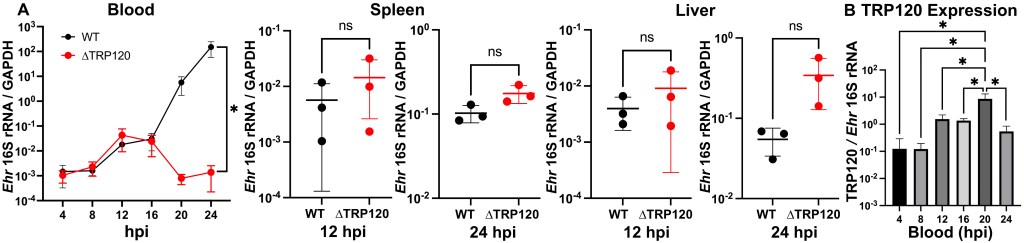

🐁 In mice:

Both WT and ΔTRP120 still caused severe disease, similar cytokines, similar tissue infection.

🩸But in the blood???

ΔTRP120 was basically GONE in the bloodstream within 24 hours, while WT skyrocketed.

So it’s like:

TRP120 is not needed to wreck the house…… but it IS needed to stay in the driveway where the Uber (tick) can pick you up. 😭🧛♂️

No TRP120 = no blood bacteria = ticks leave empty-handed.

🧠 How does TRP120 do this? (aka the immune cell “traffic” drama)

This part is my favorite because it’s so sneaky.

Your immune cells don’t just float forever — they “exit the highway” (blood vessel) and go into tissues to do work.

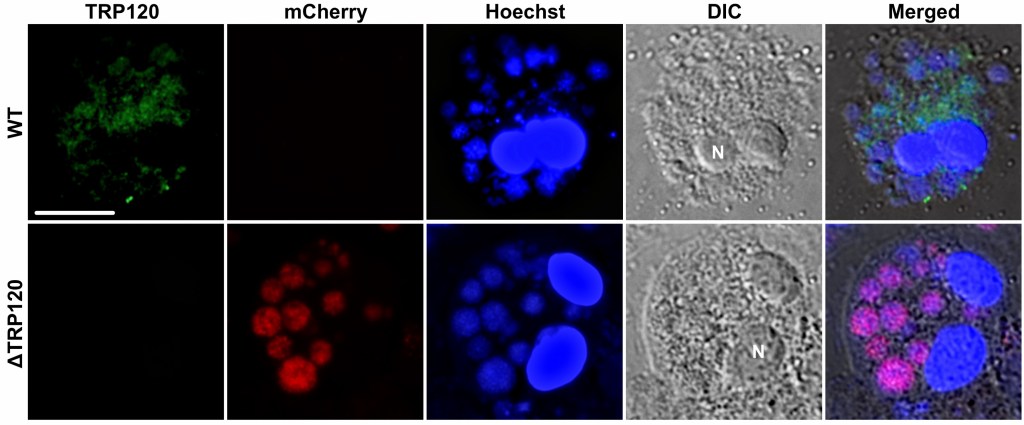

I found that TRP120 is mostly released out of infected cells (over 90% secreted), meaning it can act like a message affecting other cells and the cell itself (autocrine + paracrine effects).

And when monocytes were exposed to TRP120, they showed lower levels of surface markers Ly6C and CD11b, which are related to migration/transmigration behavior.

Meanwhile, without TRP120, infected monocytes rapidly left the blood and moved into tissues, which explains why blood levels of ΔTRP120 crashed.

So TRP120 is basically telling infected immune cells:

“Stay. In. The. Blood.” 😤🩸

“Don’t go exploring tissues yet.”

“The tick is coming.” 🕷️

It’s literally bacteria doing vector pickup scheduling.

💘 The romance ending: if you add TRP120 back, the blood bacteria comes back (a little)

To see if the ΔTRP120 phenotype was truly a TRP120 problem (and not just the bacteria having a bad day 😅), I ran a classic rescue experiment:

I gave the mutant a TRP120 “plus-one” by ectopically expressing TRP120 in ΔTRP120-infected HEK293T cells through transfection with a plasmid encoding codon-optimized 3×FLAG-TRP120.…… Okay, PAUSE! ⏸️ Apologies for the technical jargon spiral! I will not be peer-pressured into writing like a normal scientist. 😂

Anyways…… Basically, I ‘lent’ the mutant bacteria TRP120 again — by having other cells to produce extra TRP120 protein for them.

We injected those mutant bacteria—now ‘borrowing’ TRP120 from us—into mice, and they were able to hang out in the bloodstream longer, showing TRP120 helps the bacteria persist in the bloodstream, basically keeping them ‘on the menu’ for ticks to pick up during feeding.

So, the big takeaway, my paper shows that:

TRP120 is required for sustained bacteremia… but not required for tissue infection or fatal disease.

Ehrlichia isn’t just trying to cause disease — it’s trying to stay in the ecosystem. Tick-borne pathogens have to think one step ahead: they need to survive in the bloodstream long enough to be picked up by the next tick during a blood meal, because that handoff is what keeps them circulating in nature.

In that sense, they’re surprisingly strategic. Instead of killing the host too fast (which would end the trip early), they often strike a balance —persisting quietly, keeping bacteremia going, and basically hanging around in the blood like “hey tick bestie, whenever you’re ready 😌” It’s not just infection — it’s transmission planning!

And in case you’re wondering what TRP120 stands for: it’s short for Tandem Repeat Protein, ~120 kDa. If I were allowed to rename it 😭 (which I’m definitely not), I’d still keep the name TRP120—but I’d make it stand for Tick-Ready Protein 120. LOL.

😳 Anyways…… if you want to read the real paper in a socially acceptable way (aka the version my mentor wrote), instead of my chaotic narration, here’s the link: